Arthur And The Shared Spaces

Arthur Harris had opinions. Not little ones. Big, stompy ones that came in, boots first, and kicked the doors off.

He was in his sixties, hair still hanging on, just about, like it had signed a short‑term contract. Thick glasses. Permanent can’t‑be‑arsed stubble. Face like he’d been asked to share his chips.

He lived in Lower Twaddle, North Midlands, the bit they never put on postcards. Two‑up, two‑down, straight on to the pavement, traffic close enough to nick a fag off. No garden. Arthur reckoned gardens were for people who liked plants more than people.

“Aye. Dead right, that is.”

The words just dropped in.

Arthur paused. Looked round the living room. Nobody.

“You talking to me, Arthur?”

“Who else am I talkin’ to, duck? Ghosts?”

“I’m just checking.”

“You the one writin’ this?”

“Er. Yes.”

“‘Hair hanging on’” He sniffed. “You saying I’m goin’ bald?”

“No. I’m saying your hair is… short.”

“Well say short then. Don’t be clever. Clever gets twatted.”

He picked at a bit of stubble, waiting.

“Well? Crack on then.”

Mrs Gabblethorpe had emailed him. Of course she had. Mrs Gabblethorpe emailed everyone. She was chair of the town committee, the residents’ association, the “Friends Of Something Or Other”, and probably the Moon. If you could have a meeting about it, she was in charge.

Arthur had sent an email first, about this new “shared space” idea down the High Street. Take away the kerbs. Mix cars, bikes, people. Let them “negotiate”.

“Negotiate me arse,” Arthur had muttered, typing with one finger and a lot of fury.

“Oi. Author.”

“Yes, Arthur?”

“Make sure you put this bit in, right. Shared spaces are stupid. You’re asking for some pillock on a bike to wipe out half the town”.

“I’ll capture the gist, yes.”

“Don’t ‘gist’ me, pal. Just write it.”

He got dressed like he always did when he was off to start trouble but pretend he wasn’t. Black T‑shirt. Sleeveless jacket.

“Not a gilet. Say gilet and I’m walkin’ out this story.”

“Jacket. Got it.”

Work boots, laces double‑knotted, mud like a badge of honour. The sun was already belting down on Lower Twaddle, so he dragged on his baggy walking shorts, pockets like caves.

He stepped out. The street shimmered. Warm tarmac, cut grass, someone’s washing powder, bread baking somewhere round the corner.

“Hate that,” Arthur said.

“The bread?”

“Yeah. Smells like adverts. Don’t trust it.”

He cut through a jitty behind the shops, the little cut‑through where the bins lived and teenagers learned to smoke. Out onto the High Street. There it was: The Brew Stop. His café. His table. His view.

And Mrs Gabblethorpe. Already sat at his table. By the window. Like she’d paid rent.

“Oi. Writer lad.”

“Yes?”

“What’s she doin’ there already? I wanted to be there first. I’m supposed to make an entrance. You’ve ruined me entrance.”

“I thought it’d be funnier if you were already on the back foot.”

“What if I just don’t go in then, eh? Story over. Big dramatic fade to black.”

“You will go in, Arthur.”

He grunted, shoved the door. Bell jangled like it was panicking.

“Morning, love,” he called to Sarah behind the counter. “Usual, if you don’t mind.”

Usual meant a large cappuccino and that billionaire caramel slice that came with its own health warning. Chocolate thick enough to resurface the ring road.

“Morning, Arthur,” Sarah said. “Alright, Mrs Gabblethorpe?”

“Good morning, dear. I’ll have a fresh Earl Grey, if I may.”

Arthur’s head snapped round.

“Oh no. No chance. I’m not buyin’ her bloody tea.”

“It’s fine, Arthur,” the voice said, patient. “Sarah’s got it.”

“I’ll put it on the loyalty card,” Sarah whispered. “Don’t tell my boss.”

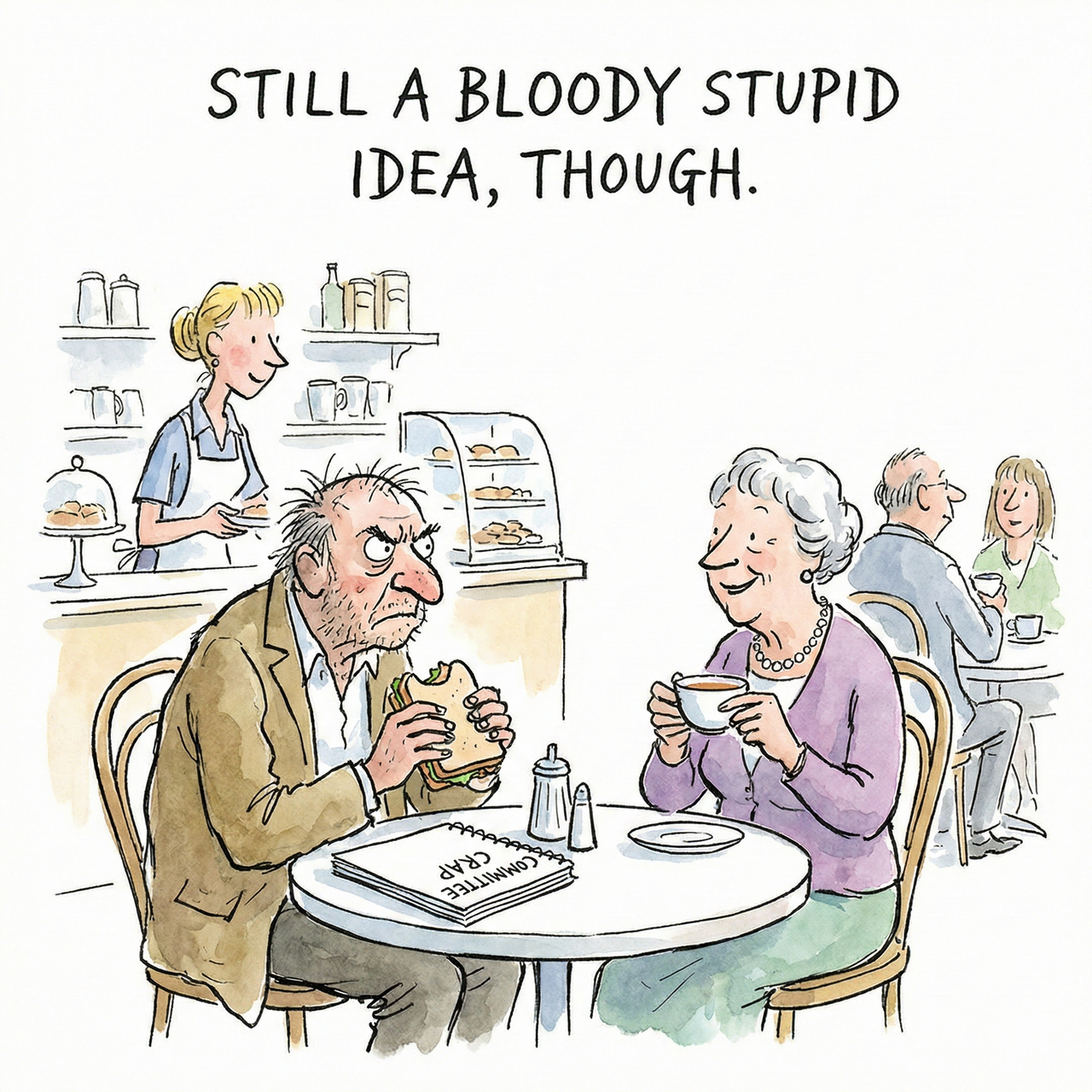

Arthur dropped himself opposite Mrs Gabblethorpe and dug out his notebook. The cover said “Shopping List” but he’d scratched it out and written “Committee Crap” over the top. The first page just said “POINTLESS BOLLARDS” six times, in biro that had nearly gone through the paper.

“Right,” he said. “Let’s not prat about. Shared spaces down the High Street. No.”

He drew a big cross in the air.

“Just no.”

Mrs Gabblethorpe tried a smile. It didn’t suit her. Her face creased up like a dog’s backside under a Sunday hat.

“If I could just—”

“No, you’re alright. You had your chance. Now it’s me. You lot on these committees, I swear. Ask you to design a horse and we end up with a bloody camel. With handlebars.”

He went at the caramel slice, bit too big, crumbs everywhere. Every word came out with shrapnel.

“You can’t have flamin’ cyclists hurtling down the path—path, that’s what it is, not a racetrack—tight shorts, stupid helmets, scarin’ folk who are just tryin’ to walk to Greggs without gettin’ killed.”

“Arthur—”

“Old dears with their trolleys, little kids lickin’ ice creams, next minute, whoosh, Lycra up their backsides—”

“Arthur!”

“WHAT?”

The café stopped. Spoons froze. Milk frother hissed like it was gossiping.

Sarah stood by the machine, half‑smile, half‑wince.

“Council scrapped it last week,” she said. “The shared space thing. They voted against it. It’s not happening.”

Arthur stared.

“Not… happening?”

“No, duck. Mrs Gabblethorpe just wanted to tell you nice and calm, before you started a riot.”

Mrs Gabblethorpe lifted her cup. Tiny sip. Saucer back down. Like she was handling explosives.

Silence. Chair creak. Someone coughed. Outside, a bus wheezed past.

Arthur looked at his notebook. At his pen. At his caramel slice, now mostly air and crumbs.

He snorted.

“Still a bloody stupid idea, though.”

He took another bite, just in case someone tried to argue.