The Unfortunate Afterlife of Clive

Clive died on a Thursday….

He’d wanted Wednesday. The bins went out Wednesday. He didn’t want to be outlived by his wheelie bin. But his heart had other ideas. His heart and gravity. They got together, the two of them, halfway through a bit of plumbing he’d no business doing, and that was that.

Maureen found him under the downstairs toilet. Spanner in his hand. Face like a slapped arse.

— Oh for God’s sake, Clive.

She looked at him.

—I told you that pipe wasn’t looking at you funny.

She rang the ambulance. Then she rang Sheila from Bingo. The ambulance was the right call. Sheila was not.

Sheila prodded his sock.

—Is he—

—Either that or he’s taken up yoga, said Maureen.

The paramedics came. They muttered things. Intermediate rigour. Amateur bloody plumbing. They took him away.

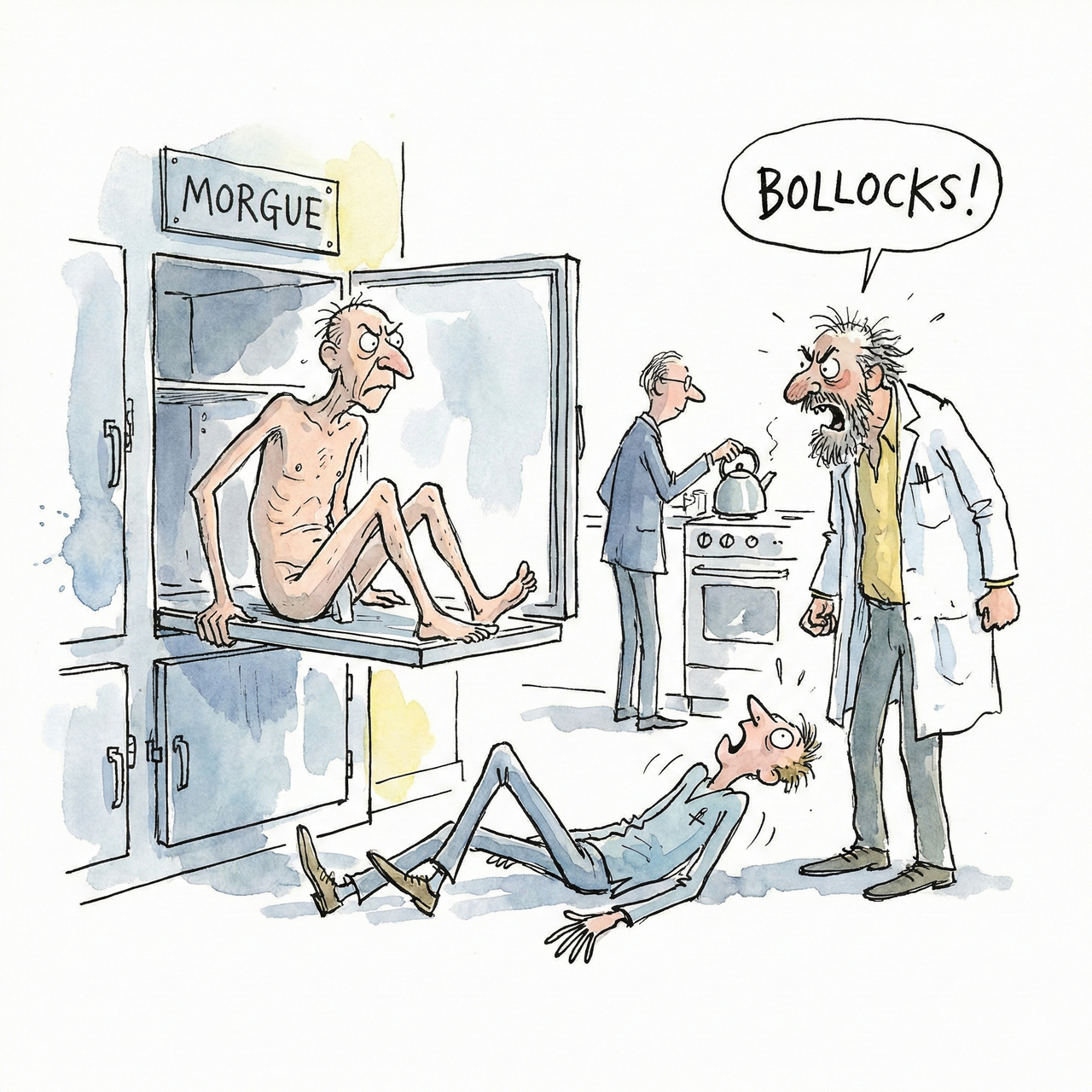

Three days later Clive woke up in a drawer.

A refrigerated drawer. In the morgue.

He was naked. He was cold. He was very much not cremated.

—If this is heaven, he said, —It’s got appalling climate control.

A junior technician fainted. A senior technician said BOLLOCKS very loudly and then said it again. The coroner put the kettle on.

—I’m not doing undead paperwork without biscuits, he said. —Not after last time.

—Last time? said Clive.

—Don’t ask.

They gave him a blanket. They gave him tea. Scalding. They gave him a brochure. SO YOU’VE BEEN DECLARED LEGALLY DECEASED: A CITIZEN’S GUIDE.

Clive read it.

—It says I have to reapply for my National Insurance number.

—That’s if you’re planning to rejoin the workforce, said the coroner.

—I’ve just come back from the dead. I haven’t lost all sense.

He went home.

Maureen opened the door. She was holding a mop. She looked at him the way she looked at him when he tracked mud in. Which was the way she always looked at him.

—You’re dead, she said.

—I got better.

—You’re dripping on the doormat.

—Maureen—

—On the doormat, Clive.

She let him in. Eventually.

She’d donated his fishing gear. She’d cancelled his dentist. She’d sold his recliner — his recliner, the one that reclined exactly right, the one he’d spent four years breaking in — to Barry next door.

She was calling Barry “Baz” now.

—It was my chair, Maureen.

—You weren’t using it.

—I was dead.

—Exactly.

—You can’t just—

—I can.

—But—

—I did.

The Church wouldn’t update his gravestone. They wanted proof of sustained reanimation. Sustained. Like he had to keep it up for a bit before they’d believe him.

The bank froze his accounts. Pending metaphysical clarification. He didn’t know what that meant. They didn’t know what it meant. Nobody knew what it meant. But it meant no money.

Tesco banned him. There’d been an incident. The self-checkout, three packets of custard creams, and a bishop. The bishop was startled. It wasn’t Clive’s fault.

—It scanned me, he said.

—You leaned on it, said the manager.

—And it told me to place myself in the bagging area.

—Sir—

—Place MYSELF.

—I’m going to have to ask you to leave.

—I’ve just come back from the dead.

—That’s not really a Tesco issue, sir.

He moved into the shed.

Not a shed. THE shed. His shed. His Fortress of Lawnitude. He rigged up a kettle. He found the transistor radio. He set up the deckchair, the one with the stain he’d never explained and never would.

He was alive. He was technically illegal. He was in the shed.

He judged people. Quietly. Anyone who misused a spanner. Anyone who called Barry “Baz.” Anyone who sold a man’s recliner while he was temporarily dead.

—If I die again, he said.

Nobody was listening.

—I’m taking Maureen’s bloody geraniums with me.